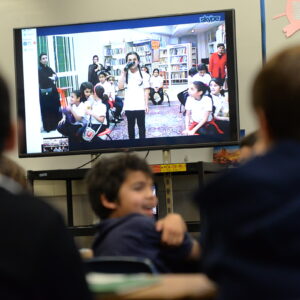

Renowned travel and nature author David Quammen appeared via Skype to a large crowd of students at Nichols Hall auditorium on Oct. 30 to discuss his experiences in writing his latest non-fiction book, “Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic.”

From his home in Bozeman, Mont., Quammen started by talking about his authorial origins as a fiction writer in the 1970s. He later joined the outdoors magazine “Outside” as a columnist, originally planning to contribute for just one year, which ended up being 15.

He began writing non-fiction in the 1980s, and last year released “Spillover,” his 10th non-fiction book, which covers in depth how viruses travel from humans to animals. The book tells the history and development of this study, covering such key points as the AIDs epidemic, the early-2000s SARS outbreak, the spread of diseases such as Ebola and various influenzas and more.

The book, which was in the works for several years, took Quammen to many very interesting places. He recalled one night in Bangladesh, where he was observing veterinarian and epidemiologist Jonathan Epstein as he captured fruit bats in an effort to discover how the Nipah virus was infecting the local population. The job required a hazmat suit and goggles, which were constantly fogging up and obscuring his vision, increasing his anxiety that an infected bat may bite or scratch him.

On another trip, to China, Quammen and the researcher he was with squeezed through narrow caves, also looking for bats, but this time without the hazmat suits. When Quamman asked the researcher why they were not wearing protective gear, the researcher replied that oftentimes researchers take a “calculated risk.”

“The developed world is very vulnerable,” he said, citing the SARS outbreak, which began when a woman traveling from Hong Kong brought the virus with her to Toronto. Another modern example was the occurrence of the West Nile virus in New York City in 1999.

Although developed countries have more resources to deal with these outbreaks, even in undeveloped areas these viruses can pose a significant worldwide risk, he said, because viruses become more effective at infecting humans with each new case. He then stated there was a need for more international institutions dedicated to researching how viruses in animals begin to infect humans and how to prevent outbreaks.

This need has created a growing field for young scientists. A veterinarian, he said, may return to school and earn a Ph.D. in ecology. “More and more you see this kind of expert,” he said. “And most of them are young.”

As for prevention of the spread of these disease, Quammen said the biggest reason for the spread is ecosystem disruption, such as foresting and the hunting and eating of wild animals. He said that though many peoples frequently subsist on bushmeats, and that others must be sympathetic to their needs, it is necessary to help them find alternatives to prevent the spread of animal borne viruses.