This article originally appeared in the winter 2009 Harker Quarterly.

Just recently on campus, I saw a couple of students casually talking with a teacher, a common scene, especially around lunchtime and after school. They concluded their brief chat with a gentle, playful knuckle crack. Was this the new handshake in this post-H1N1 world, presumably because viruses have more difficulty jumping from knuckle to knuckle than from palm to palm? Perhaps the students taught the teacher the new handshake to assist him in being more cool.

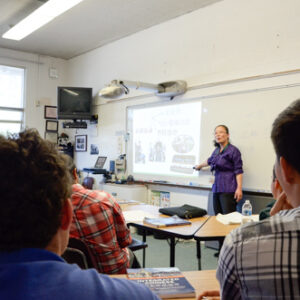

This easy, respectful exchange is one of hundreds of such exchanges that happen between teachers, staff, coaches and students daily within a learning community. Ever since Socrates debated with his students in the Agora, educators have touted the benefits of real dialogue with live human beings within proximity of each other as optimal for stimulating thought.

After a recent town meeting with upper school students, I had a student approach me privately to tell me that he benefits more in classes that have dialogue, where students are placed in a circle of desks or around the table, all facing each other. He felt that no student can hide in this arrangement, that the class worked more as a community and the dialogue pushed everyone towards better thinking. He added that when students face each other and talk about concepts, everyone becomes responsible for the learning and the discussion.

The Digital Age, however, is upending all traditional assumptions about what shape education ought to take in the future. What should schooling look like in an age where I can download all of the works of Proust on my iPhone for free? It was not too long ago that most of humanity considered owning a book a luxury. Giving lectures in the Middle Ages meant reading from a book because the lecturers, usually priests, were the only ones who owned books. Lecture comes from the Latin “legere,” meaning “to read.”

I also have downloaded most of the main texts of the seven major religions on my iPhone for free. I read from them while I am waiting for my wife in the car. There was a time when few families could afford to own the Holy Bible or even read from it. I think of the millennia of wisdom distilled into those texts compared with the ten seconds or so it takes for me to acquire them. People have lived and died by these holy texts, and I zap them into my phone while in the checkout line.

We are all struggling to envision the school of the future, or the shape that common schooling will take for most students in the future. Right now, the educational landscape seems to be fragmenting, not converging. There are more choices of structure than ever: public, private, charter, online, homeschooling and all variations in between. No one structure seems to have a claim on the future – perhaps no one structure ever will.

Proponents of online schools and homeschooling understand that students still need proms and band practice. Brick-and-mortar schools cannot fail to capitalize on the pedagogical applications of YouTube (yes, there are

plenty). Educators and parents are acutely aware of the more competitive world young people are inheriting. As Tom Friedman, author of “The World is Flat” and other bestsellers, is fond of saying, “It used to be better to be a B+ student from Brooklyn than an A student from Bangalore.” Not anymore. Anyone can compete from anywhere.

Some businesses are working under a new paradigm called “clicks-and-mortar.” Schools are doing the same. Throughout history, we developed large libraries and cultivated educated teachers and professors who slowly meted out access to knowledge through coursework and circulation desks. Now those clicks in the “clicks and mortar” model have bypassed all access controls. Learning is asynchronous, not synchronous. Students and teachers do not have to be in the same room at the same time to conduct schooling. More radically, some believe that we do not need teachers – all of the world’s knowledge exists in the “cloud.”

We have been here before. Diderot’s effort to compile huge swaths of knowledge in the “Encyclopédie,” some 35 volumes in length, typifies the Enlightenment Age’s impulse to categorize knowledge in accessible ways. It was believed that the chalkboard, film strip, radio and television would revolutionize classrooms. So far, the chalkboard has had the biggest claim to fame in that regard.

Neil Postman, author of “Amusing Ourselves to Death” and other books on education, reminds us that the invention of the printing press made traditional schooling more necessary, not less. The unprecedented access to knowledge the printing press inaugurated made it necessary to control and organize the flow of information to youngsters in age- and developmentally-appropriate ways. Traditional schooling was not made obsolete by the printing press; rather, it was made more necessary because of the deluge of information the printing press poured over the masses.

Do we have a similar condition with the Internet? Does the Internet, with its even greater and easier access to information than the printing press, make background knowledge and context that much more necessary? I will never forget a faculty meeting during which teachers were discussing the importance of content knowledge in the learning process. John Near, a beloved 31-year history teacher who recently passed away, said something extraordinary. All of his best researchers, he said, were also his most knowledgeable history students. He did not mean that they became knowledgeable history students through good research. He meant that they knew how to research, whether online or traditionally, because they already knew so much about history.

The Internet is a wonderful tool. I had to pop online several times while writing this article to confirm facts. Was it Diderot who was hired to edit the “Encyclopédie”? I could confirm this fact more quickly on the Internet than anywhere else. But I had somehow to remember Diderot’s association with the “Encyclopédie” during the Enlightenment to have a fact to confirm in the first place.

What will schools look like in the future? None of us can be sure, and there are many models up for grabs. I hope that whatever model or models hold, there is room for human exchanges and extreme care around the context of knowledge that is shared. I don’t think we can take the humans out of what is essentially a human activity. An “educated” baseball glove has all of the warmth, texture and character of the human hand that wore it for countless games and practices. Socrates may or may not have knuckle-cracked with his students, but he did touch their minds, and ours, forever.