This article originally appeared in the summer 2018 issue of Harker Magazine.

While Harker students are known for their academic achievements, they often look for ways to apply their rigorous education to situations that affect the world far beyond their school’s demarcations. To meet this demand, several programs have developed over the last two decades to give students a way to rise to challenges that people deal with in their everyday lives, or to provide possible solutions to problems just over the horizon.

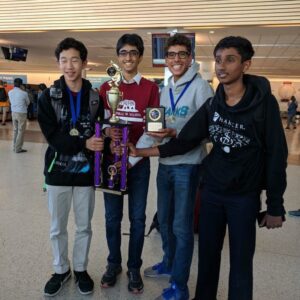

At Harker, the largest and longest-running of these programs has been Future Problem Solving (FPS), which just last year extended to the lower school. Middle school history teacher Cyrus Merrill became the faculty advisor for the program during the 1998-99 school year, and Harker FPS teams have advanced to the program’s international competition 13 times since 2002.

Since its founding in 1974 by psychologist Ellis Paul Torrance, Future Problem Solving Program International has grown to attract more than a quarter of a million participants each year in grades 4-12. Each year, students receive general topics to research in preparation for the problem scenarios that are later distributed to the participating schools. Typically, the topics involve the use of developing technologies and societal trends. This year’s topics included criminal justice, controlling the spread of infectious disease and the overabundance of toxic waste. The selected topics are approached from many angles, including civil liberties, environmental impact and the effects they have on world economies. “In FPS, we learn to analyze the same issue from 18 different perspectives, which shows us just how complex these global emergencies are,” said Meghana Karinthi, grade 12, who has been involved with FPS since grade 6.

In competition, students are given a scenario and have two hours to devise a number of possible solutions, choosing the one they feel is the best and developing a plan to implement it. It is during this time that the previous research done on the topics becomes crucial, as often the scale of the problems can be daunting. “At first, when I was in sixth and seventh grades, it was really difficult for me to comprehend this magnitude of what we were trying to solve in FPS,” said Karinthi, “but still, I was fascinated, and that fascination has stuck with me ever since.”

Because FPS requires a diverse set of skills, it has attracted students with a wide range of interests. “My sixth grade English teacher recommended me to Mr. Merrill as someone who might be a good fit for the program since I loved writing, so Mr. Merrill came up to me one day at lunch and asked me to join,” said Jessica Wang, grade 12. “A couple of my other friends were also starting FPS, and I figured I might as well try it, and as it turns out, I fell in love with it.”

Often students involved with FPS have discovered that in addition to bolstering their research skills, competing in the program has helped grow their interest in a range of topics, which has some unexpected benefits. “Since FPS covers a wide range of topics, from transportation to technology, researching those different topics in preparation for our problems is a really good way for me to learn more about things that I normally wouldn’t be looking into,” Wang said. “Because of that, I’m able to use that information for my classes too, like when different political trends my team researched were relevant to my history course last year.”

Sasvath Ramachandran, grade 8, admitted that he sometimes viewed the scenarios as far-fetched, but that they have helped him see the world in ways he previously did not. “Essentially, FPS has taught me to observe the world around me and keeps me thinking on my toes about what could improve,” he said.

Although the main goal of FPS is to train students to tackle situations that can often seem grim, the competition’s verbal presentation component – in which teams put together skits describing their solutions, often with hilarious outcomes – is a favorite of students who like to flex their creativity. “During skits, I have the chance to laugh and enjoy moments with my team, while accessing my inner creativity to put on a fun show,” Ramachandran said. Karinthi found that working with others was the greatest reward she received as an FPS competitor. “Whether it’s my actual team that I compete with, the officer team that I work with, or the middle and lower school teams that I mentor, I’ve met some incredible people through FPS who I never would have met otherwise,” she said, noting the value of short but memorable moments she has shared with her teammates. “Random moments, like sharing a bag of popcorn with my teammates while researching the next topic, or reading the string of hilarious text messages in the officers’ group chat about someone’s lost vacuum cleaner, make me realize that these people aren’t just my FPS classmates, they’re my friends.”

Giving presentations is just one of the confidence-building aspects of FPS, which emphasizes teamwork and making the most of each team member’s strengths. Wang found that this process helped her overcome initial reservations about working with people she didn’t know. “When I first joined the program, I was super shy and introverted, and I only knew a few people also in the program, which meant that I had to learn to work with people I’d never spoken to before,” she said. “By working as a part of a four-person team, I slowly became more comfortable with sharing my ideas and building off those of my teammates, and FPS is what really made me realize the value of teamwork.”

eCybermission

FPS is just one example of the opportunities students have to apply their learning to real-world problems. The middle school-based eCybermission science fair, sponsored by the U.S. Army, offers opportunities to delve into challenges affecting local communities and have a direct impact. Harker students have been entering the eCybermission competition since the 2005-06 school year, and four teams have qualified for the national finals in Washington, D.C. Unlike Future Problem Solving, students are free to choose a topic so long as it falls within one of several categories. After identifying a community problem, “students do experiments, they do surveys, they do interviews,” said middle school science teacher Vandana Kadam, who has overseen the program since the first year Harker began participating.

This year’s project – conducted by eighth graders Madelyn Jin, Clarice Wang, Emily Zhou and Gloria Zhu – investigated the causes of the wildfires that ravaged much of Northern California last fall. In the course of their research, they explored the various methods used to fight fires and spoke to a local fire official to gain his insight on how fires are contained. Their science studies at Harker also provided valuable information on “how fire reacts to different chemicals and how fire reacts to water, what makes the fire grow bigger, what extinguishes the fire,” said Wang.

Although eCybermission is a primarily a STEM competition, it is also multidisciplinary in that it makes use of a wide range of skills, such as writing and public speaking, according to Kadam. Previous projects have seen students directly engage with their communities to address potential problems. In 2010, an eCybermission team known as “Dust Busters” investigated water sources in Cupertino that were in close proximity to a quarry, and discovered that dust from the quarry was polluting the drinking water in the area surrounding the source, increasing its mercury levels. To bring attention to this issue, they presented their findings at a city council meeting. The Dust Busters went to the national competition that year.

Community presentations at schools, libraries and community centers are an important aspect of eCybermission, as they bring awareness to issues that residents may not be aware of, in addition to helping students build confidence in summarizing and presenting information on complex topics. “For the students to be able to connect to these people they’re presenting to is very important,” said Kadam. “It’s going outside of their comfort zone in a way.”

Students also learn how problems can arise in the course of developing a project, and how to deal with them in a timely manner. “We encountered a big setback while we were doing our project and we had to reorganize and change the whole project in a short period of time,” Zhou recalled. Accounting for each team member’s schedule was another hurdle, as well as a learning opportunity. “Time management was really difficult, because we had to find times to meet up and work on things as a group and with our advisor,” said Wang.

It also helps students realize the impact they can have on their communities, however small it may be. “There are problems in the community that we can solve in our little ways,” Kadam said. “They feel good that, whatever little they did, the research they have done is helpful to those people in the community.”

TEAMS

At the upper school, students each year participate in an engineering-focused competition called TEAMS (Tests of Engineering Aptitude, Mathematics and Science), formerly known as the Junior Engineering Technical Society. Upper school math teacher Anthony Silk has managed the program since 2007, and in the ensuing years, students have performed very well, with key accolades including a 2016 “Best in Nation” designation and a 2015 second place finish at the national level, as well as numerous distinctions at the state level.

TEAMS has two high school divisions – one for grades 9 and 10 and another for grades 11 and 12 – and each TEAMS competition has three components: a thoroughly researched essay on a given scenario, a multiple-choice exam containing 80 questions on various engineering problems, and a design/build stage in which teams use provided materials to complete a design challenge based on the competition theme for that year.

“I think the engineering challenge was a group favorite,” said Mohindra Vani, grade 10, from this year’s team. “It got our adrenaline pumping and it was gratifying to see the result of our labors take the shape of some tangible object because that wasn’t something we really got in the multiple choice or essay sections of the competition.” Of the three components, Silk said, “One of them is simply pure academics, one of them is more research and one of them is more practical, how you visualize the world and can you make engineering connections,” describing the various skills that come into play in the competition. “[The students are] really trying to find ways that we interact with the environment and how we can do better at that.”

As with other competitions, division of duties according to each team member’s strengths is an important element of success in TEAMS competitions. “This is done in a group of eight, and they have to work together,” Silk said. “No one student can say, ‘Well, I’ll do it all and you check my work.’ It has to be, ‘You’re the chemistry lead, you’re the physics lead, etc.’”

Silk also stressed that the competition is almost entirely student-run; he acts only as the facilitator for the multiple-choice portion. “Some schools have TEAMS classes where they meet every week,” he said. “We don’t do any of this. If this is what they want to do, I provide them with the materials, I provide them past exams so they can see how it is, but they have to get together on their own, they have to study on their own, they have to figure out how to work together on their own.”

The scheduling of the TEAMS competition often makes it difficult for juniors and seniors to compete at the national level due to internships and other obligations, but students in grades 9 and 10 have seen success at nationals on several occasions, including the aforementioned placements in 2015 and 2016, as well as another “Best in Nation” win in 2013 and a fourth place national finish last year.

Silk says, however, that what’s important for the students is not to chase accolades, but to enjoy the act of solving problems through engineering. “I think that’s really important for our kids, that they’re doing this purely for the enjoyment of it because they want to do it and they’re going to drive themselves to do it,” he said. “Not because of a grade, not because somebody’s telling them to do it.”

![[UPDATED] Future Problem Solving Team Advances to Finals at International Competition IMG_0022](https://news.harker.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/IMG_0022-e1461013196982-300x300.jpg)