This article originally appeared in the summer 2014 Harker Quarterly.

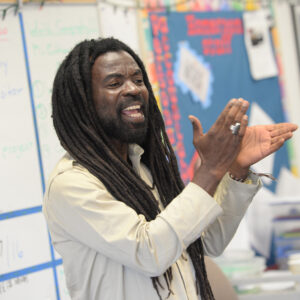

Education activist Kakenya Ntaiya, Ph.D., founder of the Kakenya Center for Excellence, gave an eye-opening and inspiring talk in early May as a guest of the Harker Speaker Series. After being introduced by young activist Aliesha Bahri, grade 8, Ntaiya first took the audience back to Kenya, where she was born into one of 42 tribes, each with different languages, customs and traditions. Her tribe, the Maasai, “are very, very famous,” she said, known for the jumping dances performed by the tribe’s warriors and their red attire.

By the time she was 5, Ntaiya’s marriage had already been arranged. “They put a [necklace] on my neck, and that was always a reminder for me that I have a husband,” she said. Ntaiya attended school as a child, because she remembered that her mother had wished she could have stayed in school longer. “She would tell us, ‘Do you see the member of parliament? I was smarter than him in class,’” she recalled.

At the age of 12, Ntaiya realized that her days of attending school could soon end, as she was nearing the day when she would undergo the Maasai’s female genital cutting ritual – a painful and often life-threatening procedure – and would soon thereafter be married. “I had to come up with a way of escaping that,” she said. Ntaiya normally would have to send her mother to inform her father of her intentions to continue school. However, fearing that her mother would be beaten for delivering bad news, she delivered the message herself as tradition forbid him from beating her. She told him she would go through with the cutting if she could be allowed to continue her education. If he refused, she would run away, bringing shame upon on him. Her father agreed.

During high school, Ntaiya applied and was accepted to Randolph-Macon Woman’s College in Virginia. Initially, she faced resistance from the other villagers, but managed to convince them to pay for her trip overseas to begin her college career. She later learned much about the plight of girls around the world who did not have access to a good education. “I started questioning every little thing because what I was reading in books was my life,” she said.

Her newfound purpose led her to work at the United Nations after finishing her undergraduate degree. She also visited home on a number of occasions, often hearing “horrible stories” about the people she once knew in her village. Moved by these accounts, she decided to build a school for girls.

In May 2009, the Kakenya Center for Excellence opened in Kenya for girls in grades 4-8. It now serves 170 students in grades 1-8. The school provides uniforms, books and other materials, but it was the added importance of providing lunch that caught Ntaiya by surprise. “It had never registered in my mind that that actually made a difference,” she said. Normally, girls would only have a cup of tea in the morning, walk anywhere from 2 to 5 miles to school and not eat until the evening, “because you can’t just run another 5 miles to go have lunch.”

Qualified teachers were also very important. “We had teachers who are very, very caring,” she said, “teachers who came there, who knew that it’s a girls school and all the girls have dreams and we’re going to cultivate those dreams to become a reality.” This was crucial because girls are often neglected at school, as they are assumed to be getting married. Toward the end of her talk, Ntaiya spoke briefly about her work with Girls Learn International, which partners schools in the United States with those in other countries where girls struggle with access to education. “If you look at me, if I got the mentorship that I needed when I was 12 years old, where do you think I would be?” she asked. “If we can give these girls that mentorship, if we can mentor them … you will see a different world.”