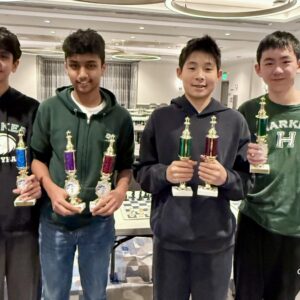

WORDS BY ALYSSA AMICK ’15 AND PRISCILLA PAN ’15

PHOTOGRAPHS BY SHAY LARI-HOSAIN ’16

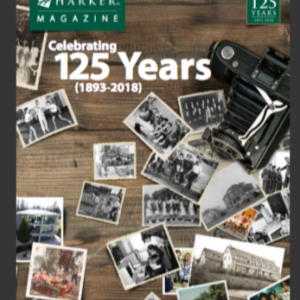

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Wingspan, a Harker student magazine, on Jan. 28, 2015. It was re-published in the inaugural issue of Harker Magazine in Winter, 2016.

A blanket of white enveloped the valley, which extended for miles as far as her eyes could see. It was summer in the Valley of Heart’s Delight, which would later be better known as the Silicon Valley, where endless blossoms marked the transition from spring into the beginning of a season when she would excitedly pick cherries.

Ten-year-old Kristin Giammona ’81, now Harker’s elementary division head, frequently rode her bike down the lanes of cherry orchards in her Willow Glen, San Jose neighborhood in the 1970s. Year after year, though, she noticed more and more houses replacing the fruit trees, usurping the green, empty vastness of the Valley of Heart’s Delight.

In 1919, fruit trees were planted in approximately 12 percent of Silicon Valley’s (then the Santa Clara Valley’s) 839,680 acres, according to the County of Santa Clara’s database. Vineyards made up an additional 2,850 acres, says the History of Santa Clara County. Also, with 18 canneries, this region, with abundant job opportunities and fertile land, was one of the largest centers for American food production until the 1960s.

Socially and economically, Silicon Valley revolved around its agrarian roots. Growing up, Giammona relished in watching the seasons change through several different fruits and vegetables. A San Jose native, Giammona hails from a long line of Silicon Valley food workers; her father was both a broker between farms and grocery stores as well as a canner, while her mother was one of many who tinned tomatoes at a cannery.

In the summer, Giammona was surrounded by families who sold cherries grown in their yards. Several small stands, run by cash businesses, worked around the timing of the seasons throughout the popular hubs in San Jose.

“If you wanted corn, you knew to go to Almaden Expressway,” Giammona said. “There were different areas you knew. In Los Gatos, there was a dairy farm, and I remember driving up this dirt road and we’d get fresh eggs.”

In 2014, though, picking fresh produce is a rarity in Silicon Valley, as the majority of arable land has been taken over by city developers and technology companies. Nevertheless, traces of the valley’s agricultural past linger in residents’ memories and protected expanses of land, such as recreational orchard gardens scattered throughout the area.

Giammona’s mother, Dorothy Scarpace, recalls spending her childhood summers cutting and drying apricots with her sister. “It was really a very wonderful area because everybody got to work in the canneries, and you only had to be 14 years old to work in them,” Scarpace said. “We could work in the summertime and then save our money for school to buy our own clothes and such.”

It didn’t end there, though. Giammona’s maternal grandfather worked for a trucking company, where he hauled tomatoes for the brand Contadina.

Like Scarpace, fellow San Jose native Mike Bassoni was raised during Silicon Valley’s agricultural times. Bassoni, Harker’s facilities manager, grew up in San Jose before urbanization.

“The houses across the street from me were the end of developed San Jose [in 1947],” he said. “From that point you could run through the orchards – prune orchards and apricot orchards primarily – all the way to Blossom Hill Road.”

The early 20th century had ushered in opportunities for fruit stand workers and food brokers. The canning industry was particularly prominent after the can manufacturing process became viable during World War I.

Specifically, this procedural efficiency followed the creation of the assembly line and mechanization of factories. Tin cans filled with fruit grown in Silicon Valley soil lined supermarket shelves. People even immigrated both nationally and internationally to California to find jobs in the canning industry and to be farmers.

In 1905, Bassoni’s grandfather opened a grocery store four blocks from Japantown in downtown San Jose.

“Probably 12 or 14 of my family members all worked in the canneries,” he said. “My father drove the trucks, and his brother fixed the trucks. Many of my aunts worked on the assembly line. You had to hand-process the fruit. You literally would have an army of people watching fruit go by and see if it was bruised, or maybe had a worm in it. There was no other quality control.”

According to Bassoni, the canning industry is what made San Jose originally, so much so that the Bay Area’s economy was driven by it. That is, until the technology revolution, which led Silicon Valley to what we know it as today, dawned.

In 1938, Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard began work on a product that would eventually lead to the birth of Hewlett- Packard, the company behind the well-known HP computers. With this invention, they ignited a new tech age. Soon after came the hoard of renowned tech companies that now characterize Silicon Valley – Apple, Google, Facebook, Twitter, to name a few.

In addition, the population of San Jose swelled from below 100,000 during Bassoni’s childhood to over a million. “In my lifetime, I’ve seen the population of San Jose double tenfold,” Bassoni said. “I used to be able to get on my bicycle and within about four, six pedal strokes, I could be out in the country; I could be out in orchards. You can’t do that anymore. It’s hard to escape what your generation views as just norm. If you get to a high point and you look across the valley, you see structures.”

As business offices and homes went up, the orchards came down.

The technology industry also displaced the valley’s food-based industries such as canneries, dislodging jobs that people had relied on. According to Giammona, families were unable to keep up with the times, as canning was the only life they knew.

“Because the food industry was such a big part of my family, it was sad to see my dad’s business kind of drop off,” Giammona said. “The images of big [and] open trucks carrying tomatoes that [we’d] see all the time in the summer, just gone.”

With the disappearance of canneries, Scarpace believed that her children missed out on firsthand insight into their roots.

Giammona also felt that a distinct, natural beauty was replaced in the valley when its vast land was supplanted by big companies, urbanization, and other industries that placed buildings in their stead.

“I think in some ways it’s kind of sad because the valley was so green and so beautiful, and all these buildings have been built upon soil that’s very fertile,” Giammona said. “I think we’ve really lost an agricultural area that was really important to California, and now you have to import things that you could have grown here.

“It’s just so overbuilt, and when you visit other areas like Italy and even other states, you see that they’ve preserved those areas, and we just really haven’t. You’re wasting all this beautiful soil on building buildings on top instead of putting the housing farther out or in different areas. It’s unfortunate it wasn’t thought out; how do you do both?”

An increasing resistance to the urbanization has recently gained momentum by local farmers and ranchers, many of whose families have stayed in Silicon Valley for generations in an attempt to revive the old agrarian culture of San Jose.

The family of Harker alumna Franny Thompson ’05 owns a cattle ranch, Rancho Yerba Buena, in Evergreen, San Jose. The property has belonged to the family for four generations, since 1910. Although originally a dairy, the family gradually added an orchard with apricots, prunes and walnuts. Today, it focuses on beef cattle.

“We feel proud that we get to help carry on the legacy of our family’s ranch,” Thompson said. “Our family has a deep-rooted history in the Santa Clara Valley because of our ranch, and there is definitely a sense of feeling connected to the past and looking towards the future, which is both interesting and exciting during this ever changing time in the area.”

Despite interest from developers for their land, the Thompson family chooses to keep the property. It remains as one of the few surviving ranches in the area.

Similarly, the Corn Palace, located in Sunnyvale, has been a landmark to locals since 1926.

The 20-acre food stand co-owned by brothers Ben and Joe Francia is frequently used by their children and grandchildren to grow corn, among other produce. Despite several multimillion dollar offers to buy the land and not to mention the townhouses and condominiums encroaching on their property, the brothers refuse to part with their family’s land.

Farmers and ranchers who do not sell their Silicon Valley land cultivate it through a distinct market niche of fruit stands, grocery store produce sections and weekly farmer’s markets.

The Old Olson Cherry Orchard, located off Mathilda Avenue in Sunnyvale, continues to produce cherries to this day. For four generations, the Olson family has worked in the orchards growing cherries, and for a short while apricots and prunes. Though their fruit stand sits in the same location it did in 1899, it now shares the same parking lot space with a nearby Chipotle, Starbucks, and a new Trader Joe’s less than 100 yards away.

Some farmers, however, have taken advantage of the urbanization. Andy Mariani, owner of Andy’s Orchard in Morgan Hill, for instance, benefited from the recent trend to consume whole and artisanal foods by easing his orchard’s transition into the technological era.

“When you have agriculture near an urban area, [you have] a different outlook,” Mariani said in a phone interview. “[I grow fruit] that you can demand a higher price for instead of just growing commodities. I’m trying to grow fruit like my parents did, but I have the advantage that this whole [food] trend has come about.”

Several towns have also set aside parks and preserves to capture the beauty of what was nearly 100 years ago, and cities have started to preserve or replant orchards. The Los Altos library sits next to apricot trees, and Sunnyvale has a Cherry Orchard Park.

Furthermore, programs urging citizens to return to growing some of their own produce, including Silicon Valley Grows, have sprung up. Silicon Valley Grows is a group started by six local libraries to “lend” seeds to members. They plant and grow the crop, collect the seeds after harvest, and return them to the library for others to use.

In an announcement of the program, the group elaborated on the organization’s goals.

“By growing and saving heirloom seeds, home gardeners can help maintain diversity in the food supply, preserve our cultural heritage, and generate seeds for seed libraries,” wrote Silicon Valley Grows on the Santa Clara County Library website.

The cultivation of the memory of Silicon Valley’s agricultural days is manifested on the Harker campus as well. The Class of 2014 recently gifted an orchard of apricot, apple and citrus trees to the school in honor of Jason Berry, an upper school English teacher who passed away in 2013.

“The class gifted the Orchard Garden in honor of the South Bay’s agricultural roots,” said Christopher Nikoloff, head of school, in a schoolwide email. Now, students have the opportunity to sit on benches and enjoy the beauty that once filled almost all of the valley.

Although the technology incubator of the Silicon Valley continues to expand, those who grew up from a different legacy remember a distinct connection to the land. “I grow fruit,” Mariani said. “To me that’s an art — orchestrat[ing] the sun and the soil, [watching] people bite into it and say, ‘That’s the best fruit I’ve ever tasted.’ Or a little kid tasting [the fruit], and he says, ‘This is better than candy.’ That’s very satisfying.”